Tim Tyson, author of Blood Done Sign My Name, on the Civil Rights Movement:

"In fact, the movement was like a quilt—it was a work of many hands, a blanket of many patches, brought together just as quilts are often brought together, by neighbors and friends and family working together among the people they know. It would be misleading to think of one individual as having had the most impact. "

Sour Grapes Post Election 2012

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

Some Controversy Over Sojourner . . . .

Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I A Woman?”

Speech given in 1851 at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio.

"Look at me. Look at my arm. I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me - and ar'n't I a woman?

I could work as much and eat as much as a man, (when I could get it,) and bear de lash as well - and ar'n't I a woman?

I have borne thriteen chillen, and seen 'em mos' all sold off into slavery, and when I cried out with a mother's grief, none but Jesus heard - and ar'm't I a woman?

...Den dat little man in black dar, he say woman con't have as much right as man 'cause Christ wa'n't a woman. Whar did your Christ com from?...From God and a woman.

Man had noting to do with him....'Bleeged to ye for hearin' on men, and now old Sojourner ha'n't got nothin' more to say."

- Sojourner Truth (Isabella Van Wagner), 1863

Uncovering Allusion: From Sojourner Truth to Talib Kweli – Poetry Deconstruction No. 1

Speech given in 1851 at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio.

"Look at me. Look at my arm. I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me - and ar'n't I a woman?

I could work as much and eat as much as a man, (when I could get it,) and bear de lash as well - and ar'n't I a woman?

I have borne thriteen chillen, and seen 'em mos' all sold off into slavery, and when I cried out with a mother's grief, none but Jesus heard - and ar'm't I a woman?

...Den dat little man in black dar, he say woman con't have as much right as man 'cause Christ wa'n't a woman. Whar did your Christ com from?...From God and a woman.

Man had noting to do with him....'Bleeged to ye for hearin' on men, and now old Sojourner ha'n't got nothin' more to say."

- Sojourner Truth (Isabella Van Wagner), 1863

Uncovering Allusion: From Sojourner Truth to Talib Kweli – Poetry Deconstruction No. 1

Quilted Mammy Pattern & A Poem

Another poem that touched me in a special way....

"Love is a won’erful thing. A mother al’ays loves her chillun. Don’t care whut dey do. Dey may do ‘rong but it’s still her chile.

Den dere is de love uv’ va ‘oman fer her man, but it ain’t nut’in lack a mother’s love fer her chillun.

I loves a man when he treats me right but I ain’t never had no graveyard love fer no man...."- Sarah Fitzpatrick, former slave, 1938

Sorry, did not pick up who printed, or deserved credit. Simply scanned internet pg.

QUESTIONS ABOUT THE TRADITION OF QUILTING:

What are some of the reasons that these women quilted?

What do these reasons suggest about what women value?

What do they suggest about women's activities and roles in families and society?

What do they suggest about women's personal lives, professional lives, creative lives, families, communities, modes of expression?

What are some of the reasons that these women quilted?

What do these reasons suggest about what women value?

What do they suggest about women's activities and roles in families and society?

What do they suggest about women's personal lives, professional lives, creative lives, families, communities, modes of expression?

Another good visualization of migration patterns

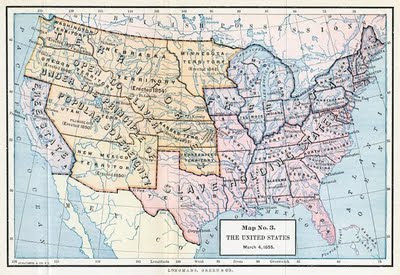

1855 Map of Slave Holding States

You might wonder, as I sometimes do.... why this intent drive to see the past historical events, authors and landscape of America.... 1800 and before.

You might wonder, as I sometimes do.... why this intent drive to see the past historical events, authors and landscape of America.... 1800 and before. Why.... I want a full context in which to view the life of my Grandad Sipuel,,,, and Great Grandmother Lucinda Smith. Even earlier times in which their mom and dad lived.

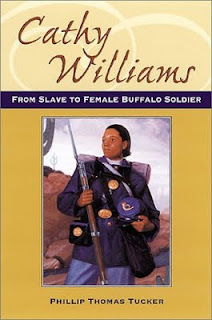

Another Book I want to read......Cathy Williams: From Slave to Buffalo Soldier

Once a slave in Independence, Missouri, Cathy Williams lived andworked in the 'big house' as a servant to its mistress. And thoughbeing a house servant carried greater privilege and status thanthat of the field hand, Cathy began to resent the menial tasks she performed as much as she resented her masters.

After the death of her owner, and having the good fortune of not being sold to pay debts, Cathy realized that the fundamental premise of slavery was a lie and this life was not her chosen destiny. So in November 1866 she disguised herself as a man, used the name William Cathay, and enlisted in Company A, 38th U.S. Infantry and became a Buffalo Soldier. As the first and only African American woman to serve in one of the six black units formed following the Civil War. Interestingly enough, Williams was able to become a member of the Army without detection of her sex, and it was imperative that she keep her true identity unknown. Her adventures took her from Missouri to the Mexican border where she served for nearly two years. After her military career Cathy did not envision returning to her roots in Missouri, plus her heart was now in the West. So she married and created a life for herself on the Western frontier, as a business-woman in Trinidad, CO.

There is much contention surrounding the validity of Cathy's story. Historians claim Tucker's only source about Williams' alleged service as a Buffalo soldier is based on a newspaper account published in 1876 and that there are no official records in existence to authenticate her Civil War service. Some believe it was easy for Williams to get discharge certificates from the 'real' William Cathay and pass it off as her own. And that 'Far too many of the speculations about Williams are colored by a 21st century "politically correct" perspective'.

Yet others offer a more positive analogy, "Phillip Thomas Tucker the prize-winning author of The Confederacy's Fighting Chaplain tells this remarkable tale of Pvt. William Cathay of Company A, 38th U.S. Infantry, who in fact was a big-boned, 5' 7" black woman named Cathy Williams. This is a unique story of gender and race, time and place.

Tucker's work is a recommended read that reaches across categories, from American, African American, and military history to Western and women's history." -- Thomas J. Davis, Arizona State Univ.

Regardless of the controversy, this was a fascinating story presented more in the vein of a documentary than a novel and it allows readers to experience a non-traditional, non-typical life for a 'Colored' woman in the 1800's. Tucker uses this storyline to captivate and educate, and he introduces a believable character who unknowingly and unintentionally charted a course for the role of today's women in all branches of the military. This story vividly brings to life another chapter of our colorful history.

Reviewed by aNN Brownof The RAWSISTAZ Reviewers

Author Rita Williams

A sobering survival story of the heart, mind and soul!

In this book, Rita Williams' accounts of her childhood and coming-of-age provide a keenly focused view into the lessons and hardships of poverty and racial discrimination, not to mention puberty itself. Making these lessons much more compelling than most, the turbulence in Rita's young life plays out against a backdrop of the stunning beauty and cruel harshness of the Colorado Rocky Mountains, all of which is described with magical clarity by Ms. Williams.

Orphaned at a young age, Rita takes the reader along with her as she is flung by wicked fate into an unforgiving life under the stern guardianship of her "Real McCoy" Aunt Daisy, a hunting guide and trapper in the mountains of the Colorado wilderness. Tough as any mountain man, Aunt Daisy is not ready for, nor able to coddle, a small child. Little Rita must toughen up to the mountaineer's lifestyle, or else! Funny, heart wrenching, and often just plain shocking, Rita Williams' book exudes a fearlessness that few writers ever muster. Powerful, courageous books such as this one often change minds and opinion. "If The Creek Don't Rise" shines bright light into dark corners of human relationships and emotions - corners that many writers are fearful to even obliquely illuminate, especially when the subject at hand is purely personal.

In the end, this book leaves the reader with a tremendous appreciation for not only the hardships of others, but also with an increased self-awareness. Ms. Williams' efforts are unique in that her book is not a "mountain wilderness survival story" about a plane crash or stranded, lost campers running out of food or freezing to death. Rather, it is a mountain wilderness survival story that is just as perilous nonetheless. It is the mind and soul, however, at risk of a "starvation and freezing death" in the high mountains.

An amazing tale of tremendous courage and a survival story like no other, this book is a must-read!

In this book, Rita Williams' accounts of her childhood and coming-of-age provide a keenly focused view into the lessons and hardships of poverty and racial discrimination, not to mention puberty itself. Making these lessons much more compelling than most, the turbulence in Rita's young life plays out against a backdrop of the stunning beauty and cruel harshness of the Colorado Rocky Mountains, all of which is described with magical clarity by Ms. Williams.

Orphaned at a young age, Rita takes the reader along with her as she is flung by wicked fate into an unforgiving life under the stern guardianship of her "Real McCoy" Aunt Daisy, a hunting guide and trapper in the mountains of the Colorado wilderness. Tough as any mountain man, Aunt Daisy is not ready for, nor able to coddle, a small child. Little Rita must toughen up to the mountaineer's lifestyle, or else! Funny, heart wrenching, and often just plain shocking, Rita Williams' book exudes a fearlessness that few writers ever muster. Powerful, courageous books such as this one often change minds and opinion. "If The Creek Don't Rise" shines bright light into dark corners of human relationships and emotions - corners that many writers are fearful to even obliquely illuminate, especially when the subject at hand is purely personal.

In the end, this book leaves the reader with a tremendous appreciation for not only the hardships of others, but also with an increased self-awareness. Ms. Williams' efforts are unique in that her book is not a "mountain wilderness survival story" about a plane crash or stranded, lost campers running out of food or freezing to death. Rather, it is a mountain wilderness survival story that is just as perilous nonetheless. It is the mind and soul, however, at risk of a "starvation and freezing death" in the high mountains.

An amazing tale of tremendous courage and a survival story like no other, this book is a must-read!

'If the Creek Don't Rise: My Life Out West with the Last Black Widow of the Civil War'

Product Description

When Rita Williams was four, her mother died in a Denver boarding house. This death delivered Rita into the care of her aunt Daisy, the last surviving African American widow of a Union soldier and a maverick who had spirited her sharecropping family out of the lynching South and reinvented them as ranch hands and hunting guides out West. But one by one they slipped away, to death or to an easier existence elsewhere, leaving Rita as Daisy's last hope to right the racial wrongs of the past and to make good on a lifetime of thwarted ambition. If the Creek Don't Rise tells how Rita found her way out from under this crippling legacy and, instead of becoming "a perfect credit to her race," discovered how to become herself. Set amid the harsh splendor of the Colorado Rockies, this is a gorgeous, ruthless, and unique account of the lies families live-and the moments of truth and beauty that save us.

A Black Woman's Civil War Memories

by Susie King Taylor:

Taylor was born a slave in 1848 on an island off the coast of Georgia. She gained her freedom and worked as a laundress for an African-American Union regiment during the war.

Taylor recalls how she learned to read and write and then herself became a teacher. She offers fascinating details about her life with the troops. She had many different duties beyond laundry service. I loved the episode where she recalls concocting "a very delicious custard" from turtle eggs and canned condensed milk, and serving it to the troops.

Taylor condemns the lack of appreciation shown for both black and white Civil War veterans. She also condemns early 20th century racism. Reading her book I was reminded of W.E.B. Du Bois' classic "The Souls of Black Folk," which was first published around the same time; I think the two books complement each other well.

Taylor ends on a note of hope and pride, noting "my people are striving" for better lives. This book is, in my opinion, an important milestone in African American literature.

First published in 1902. A new edition, edited by Patricia Romero and featuring an introduction by Willie Lee Rose, appeared in 1988. In that new intro Rose declared, "There is nothing even vaguely resembling Susie King Taylor's small volume of random recollections in the entire literature of the Civil War, or in that of any other American conflict insofar as I am aware." Indeed, this book is a rare and valuable historical document.

A Black Woman's Civil War Memoirs: Reminiscences of My Life in Camp With the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops, Late 1st South Carolina Volunteerswritten by Susie King Taylor, Patricia W. RomeroStudio : M. Wiener Pub.by M. Wiener Pub.Publisher : M. Wiener Pub.Released : 1988-04

http://www.americancivilwar.com/civilwar/searchpage/c001/A+Black+Womans+Civil+War+Memoirs.htm

Taylor was born a slave in 1848 on an island off the coast of Georgia. She gained her freedom and worked as a laundress for an African-American Union regiment during the war.

Taylor recalls how she learned to read and write and then herself became a teacher. She offers fascinating details about her life with the troops. She had many different duties beyond laundry service. I loved the episode where she recalls concocting "a very delicious custard" from turtle eggs and canned condensed milk, and serving it to the troops.

Taylor condemns the lack of appreciation shown for both black and white Civil War veterans. She also condemns early 20th century racism. Reading her book I was reminded of W.E.B. Du Bois' classic "The Souls of Black Folk," which was first published around the same time; I think the two books complement each other well.

Taylor ends on a note of hope and pride, noting "my people are striving" for better lives. This book is, in my opinion, an important milestone in African American literature.

First published in 1902. A new edition, edited by Patricia Romero and featuring an introduction by Willie Lee Rose, appeared in 1988. In that new intro Rose declared, "There is nothing even vaguely resembling Susie King Taylor's small volume of random recollections in the entire literature of the Civil War, or in that of any other American conflict insofar as I am aware." Indeed, this book is a rare and valuable historical document.

A Black Woman's Civil War Memoirs: Reminiscences of My Life in Camp With the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops, Late 1st South Carolina Volunteerswritten by Susie King Taylor, Patricia W. RomeroStudio : M. Wiener Pub.by M. Wiener Pub.Publisher : M. Wiener Pub.Released : 1988-04

http://www.americancivilwar.com/civilwar/searchpage/c001/A+Black+Womans+Civil+War+Memoirs.htm

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

Slavery in Mississippi

Slavery and Frontier Mississippi, 1720-1835

By David J. Libby

Edition: illustrated Published by Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2004 ISBN 1578065992, 9781578065998 163 pages

In the popular imagination the picture of slavery, frozen in time, is one of huge cotton plantations and opulent mansions. However, in over a hundred years of history detailed in this book, the hard reality of slavery in Mississippi's antebellum world is strikingly different from the one of popular myth.

It shows that Mississippi's past was never frozen, but always fluid. It shows too that slavery took a number of shapes before its form in the late antebellum mold became crystalized for popular culture.

The colonial French introduced African slaves into this borderlands region situated on the periphery of French, Spanish, and English empires. In this frontier, planter society made unsuccessful attempts to produce tobacco, lumber, and indigo. Slavery outlasted each failed harvest.

Through each era plantation culture rode the back of a system far removed from the romantic stereotype. Almost simultaneously as Mississippi became a United States territory in the 1790s, cotton became in cash crop. The booming King Cotton economy changed Mississippi and adapted the slave system that was its foundation. Some Mississippi slaves resisted this grim oppression and rebelled by flight, work slowdowns, arson, and conspiracies.

In 1835 a slave conspiracy in Madison County provoked such draconian response among local slave holders that planters throughout the state redoubled the iron locks on the system. Race relations in the state remained radicalized for many generations to follow. Beginning with the arrival of the first African slaves in the colony and extending over 115 years, this book is the first such history since Charles "Sydnor's Slavery in Mississippi (1933).

By David J. Libby

Edition: illustrated Published by Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2004 ISBN 1578065992, 9781578065998 163 pages

In the popular imagination the picture of slavery, frozen in time, is one of huge cotton plantations and opulent mansions. However, in over a hundred years of history detailed in this book, the hard reality of slavery in Mississippi's antebellum world is strikingly different from the one of popular myth.

It shows that Mississippi's past was never frozen, but always fluid. It shows too that slavery took a number of shapes before its form in the late antebellum mold became crystalized for popular culture.

The colonial French introduced African slaves into this borderlands region situated on the periphery of French, Spanish, and English empires. In this frontier, planter society made unsuccessful attempts to produce tobacco, lumber, and indigo. Slavery outlasted each failed harvest.

Through each era plantation culture rode the back of a system far removed from the romantic stereotype. Almost simultaneously as Mississippi became a United States territory in the 1790s, cotton became in cash crop. The booming King Cotton economy changed Mississippi and adapted the slave system that was its foundation. Some Mississippi slaves resisted this grim oppression and rebelled by flight, work slowdowns, arson, and conspiracies.

In 1835 a slave conspiracy in Madison County provoked such draconian response among local slave holders that planters throughout the state redoubled the iron locks on the system. Race relations in the state remained radicalized for many generations to follow. Beginning with the arrival of the first African slaves in the colony and extending over 115 years, this book is the first such history since Charles "Sydnor's Slavery in Mississippi (1933).

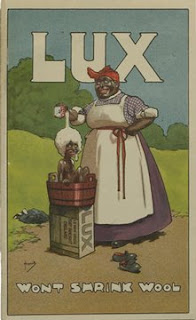

This advertisement uses both the Mammy and Coon caricatures to sell the product.

The Mammy caricature is the most well known and enduring racial caricature of African American women. The caricature depicts an obese, coarse, maternal figure with a wide grin and hearty laugh, who is a loyal servant. It was used as proof that Black women were content, even happy, enslaved.

The Coon caricature traditionally depicts Black men as being simple, lazy and too cynical to change their lowly positions. However by the 1900s, Coons were increasingly identified with young urban Black men who were seen as disrespectful to whites.

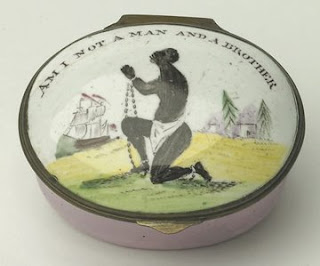

Bitter-sweet Sugar Bowl....

Slave artifacts

Slave artifactshttp://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ism/collections/legacies/windus_black_boy.aspx

Small cup with scene of a slave being whipped . . . . White china printed in green, 19th century

75 diameter x 68mm high

Small cup with a tropical scene showing an overseer whipping a kneeling and chained enslaved African and the verse:

'From Sun to Sun the Negro toils

No smiles reward his trusty care,

And when the indignant mind recoils,

His doom is whips and black despair'

The death of a slave . . . .

"When a slave die, Massa make the coffin hisself and send a couple of slaves to bury the body and say, 'Don't be too long.' No singin' or prayin' allowed, just put them in the ground and cover them up and hurry on back to that field. I'm Katie Darling."

"You now talking to a slave what nursed seven white chillum in them bullwhip days. Massa have them chillum when the war come on, and I nursed all of 'em. I stays in the house with 'em and sleeps on a pallet on the floor. Soon as I's big enough to tote the milk pail they puts me to work milkin' too. Massa have more than 100 cows and most of the time Violet and me does all the milkin'. We better be in that cowpen by five o'clock. Katie Darling."

Life on the Plantation . . . .

"My name is Mary Kincheon Edwards and I was born on the eighth of July, 1810. I was give to Master Felix Vaughn and he brought me to Texas. I nursed the Vaughns' baby son, name Elijah. I knit the socks, wash the clothes and sometimes I work in the field. I help make the baskets for the cotton. Us pick about 100 pounds of cotton in one basket. I didn't mind pickin cotton, because I never got the backache. I pick two, three hundred pounds in one day, and one day I picked 400. Sometimes the master give a prize to the slave what pick the most. I git a dress one day and a pair of shoes 'nother day for pickin the most. I so fast I take two rows at a time. My name is Mary Kincheon Edwards."

Using natural herbs for medicinal purposes:

Us boil wild sage and make tea and it smell good. It good for the fever and the chills. Us get slippery elm and chew it. Some chew it for bad feelins and some jes to be chewin.

Making soap:

"Us use ash and lye-drip for make barrels of soap. The way you test the lye is drop an egg in it, and if the egg float, the lye ready to put in the grease and make the soap. Us throwed greasy bones in the lye and the lye eat the bones. That make the best soap."

Using natural herbs for medicinal purposes:

Us boil wild sage and make tea and it smell good. It good for the fever and the chills. Us get slippery elm and chew it. Some chew it for bad feelins and some jes to be chewin.

Making soap:

"Us use ash and lye-drip for make barrels of soap. The way you test the lye is drop an egg in it, and if the egg float, the lye ready to put in the grease and make the soap. Us throwed greasy bones in the lye and the lye eat the bones. That make the best soap."

More Slave narratives.......

My name is Charity McAllister. My mother first b'longed to John Greene. She got in de family way by a white man. Dey sold my brother. He wus as white as you is.

I tell you, I was whupped durin' slavery time. Dey whupped us wid horse hair whips. Dey put a stick under our legs an' tied our hands and we could not do nuthin' but turn and twist. Dey would sure work on your back end. Every time you turned, dey would hit it. I been whupped dat way and scarred up.

Dey did not give us any holidays, [not even] Christmas in Harnett County. Dat wus 'ginst de rules. No prayer nor nuthin' on de plantation in our houses. Dey did not 'low us to go to de white folks' church. Dey did not 'low de slaves to hunt, so we did not have any wild meat. Dey did not 'low us any [garden] patches. No, sirree, we did not have any money.

We had no overseers on master's plantation, and no books and schools o' any kind for slaves. I cannot read and write. No, sir. I wish I could read and write.

Yes, sir. I seed de patterollers. Oh, oh, de Ku Klux, huh-huh. Reubin Matthew's slave, George Matthews, killed two Ku Klux. Dey double-teamed him and shot him, and he cut 'em wid de ax and dey died.

I tell you, I was whupped durin' slavery time. Dey whupped us wid horse hair whips. Dey put a stick under our legs an' tied our hands and we could not do nuthin' but turn and twist. Dey would sure work on your back end. Every time you turned, dey would hit it. I been whupped dat way and scarred up.

Dey did not give us any holidays, [not even] Christmas in Harnett County. Dat wus 'ginst de rules. No prayer nor nuthin' on de plantation in our houses. Dey did not 'low us to go to de white folks' church. Dey did not 'low de slaves to hunt, so we did not have any wild meat. Dey did not 'low us any [garden] patches. No, sirree, we did not have any money.

We had no overseers on master's plantation, and no books and schools o' any kind for slaves. I cannot read and write. No, sir. I wish I could read and write.

Yes, sir. I seed de patterollers. Oh, oh, de Ku Klux, huh-huh. Reubin Matthew's slave, George Matthews, killed two Ku Klux. Dey double-teamed him and shot him, and he cut 'em wid de ax and dey died.

Another Book Review.... "Joy My Freedom"

Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women's Lives and Labors after the Civil War written by Tera W. Hunter Studio : Harvard University Press by Harvard University PressPublisher : Harvard University Press Released : 1998-09-15

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 might have signaled the end of slavery, but the beginning of freedom remained far out of sight for most of the four million enslaved African Americans living in the South. Even after the Civil War, when thousands of former slaves flocked to southern cities in search of work, they found the demands placed on them as wage-earners disturbingly similar to those they had faced as slaves: seven-day workweeks, endless labor, and poor treatment.

In To 'Joy My Freedom, author Tera W. Hunter takes a close look at the lives of black women in the post-Civil War South and draws some interesting conclusions. Hunter's interest in the subject was initially sparked by her research of the washerwomen's strike of 1881. This labor protest by more than 3,000 Atlanta laundresses is symbolic, Hunter posits, of African American women's ability to build communities and practice effective, if rough-and-ready, political strategies outside the mainstream electoral system.

To 'Joy My Freedom is a fascinating look at the long-neglected story of black women in postwar southern culture. Hunter examines the strategies these women (98 percent of whom worked as domestic servants) used to cope with low wages and poor working conditions and their efforts to master the tools of advancement, including literacy. Hunter explores not only the political, but the cultural, too, offering an in-depth look at the distinctive music, dance, and theater that grew out of the black experience in the South.

To 'Joy My Freedom is a fascinating look at the long-neglected story of black women in postwar southern culture. Hunter examines the strategies these women (98 percent of whom worked as domestic servants) used to cope with low wages and poor working conditions and their efforts to master the tools of advancement, including literacy. Hunter explores not only the political, but the cultural, too, offering an in-depth look at the distinctive music, dance, and theater that grew out of the black experience in the South.

Yill Freedom Cried Out

"I’s born in Palestine Texas. I don’t know how old I is. I was 9 years old when freedom cried out."

Till Freedom Cried Out provides a vivid, first-hand account of Texas slave life, as remembered by those who used their newfound freedom to move away from Texas. Artist Kermit Oliver’s illustrations sensitively depict vignettes of the daily life that haunted these former slaves.

After emancipation, many former slaves saw Oklahoma as a place of opportunity, and for those in Texas, new lives were just a short trip across the Red River. They carried their memories along and reported them to WPA workers with the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s.

Till Freedom Cried Out provides a vivid, first-hand account of Texas slave life, as remembered by those who used their newfound freedom to move away from Texas. Artist Kermit Oliver’s illustrations sensitively depict vignettes of the daily life that haunted these former slaves.

After emancipation, many former slaves saw Oklahoma as a place of opportunity, and for those in Texas, new lives were just a short trip across the Red River. They carried their memories along and reported them to WPA workers with the Federal Writers’ Project in the 1930s.

Thirty-three interviews with former Texas slaves who had moved to Oklahoma are presented here, exactly as recorded by the WPA staff. Commentary by T. Lindsay Baker and Julie P. Baker provides context and sheds light on many of the details referred to in the oral histories.

Unlike most works written about slavery from the vantage point of whites, Till Freedom Cried Out is a first-hand view of everyday life for one-third of Texas’ population in 1860. These former slaves recalled family life or its absence as they were sold away from parents; their work on plantations, ruled by the overseer’s lash; being forced to satisfy the master’s desires; as well as the ways in which slaves sought solace in religious worship, music, or a walk in the woods.

Unlike most works written about slavery from the vantage point of whites, Till Freedom Cried Out is a first-hand view of everyday life for one-third of Texas’ population in 1860. These former slaves recalled family life or its absence as they were sold away from parents; their work on plantations, ruled by the overseer’s lash; being forced to satisfy the master’s desires; as well as the ways in which slaves sought solace in religious worship, music, or a walk in the woods.

T. LINDSAY BAKER, author of many books, is director of academic programs and graduate studies for the Department of Museum Studies at Baylor University. JULIE P. BAKER is director of the Layland Museum in Cleburne. They live in Rio Vista, Texas. KERMIT OLIVER is the only American ever commissioned to create artwork for the famous House of Hermés designer scarves. Oliver, a former student of John Biggers at Texas Southern University, lives in Waco and has had his work exhibited regularly for nearly thirty years.

Number Six: The Clayton Wheat Williams Texas Life Series

Till Freedom Cried Out ISBN 0-89096-736-9 $29.95 LC 96-38575. 7x10. 192 pp. 20 line drawings. Bib. Index. African American Studies. Texas History. Publication Date: August 1996

Her Act and Deed ~ Angela Boswell

Her Act and Deed:Women's Lives in a Rural Southern County,1837–1873Angela Boswell ". . . an important and original piece of work that helps fill the enormous gap that currently exists in Southern women's history."—Victoria E. Bynum, Southwest Texas State University

Deeds, wills, divorce decrees, and other evidence of the public lives of nineteenth-century women belie the long-held beliefs of their public invisibility. Angela Boswell's Her Act and Deed follows the threads of Southern women's lives as they weave through the public records of one Texas county during the middle of the nineteenth century. Her unique approach to exploring women's roles in a South that spanned the frontier, antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction eras illuminates the truths of the feminine world of those periods, and her analysis of this set of complete public records for those years challenges the theory of men's and women's separate spheres of influence.

The world Boswell reconstructs allows readers a more egalitarian, multicultural look at life: working class and poor women, both black and white, join their more affluent sisters in the pages of the Colorado County, Texas, courthouse records. Those same records reveal that the men of that world—most of them planters or farmers, the majority of them owning at least a few slaves—were a force for women to reckon with, both in public and at home. The almost constant pre-sence of men in the home and their need to uphold the dominant, slave-holding hierarchy produced a patriarchy more pervasive than that experienced by women in the urban North.

Accessible to scholars and general readers alike, Her Act and Deed represents a welcome addition to the classroom, to the scholar's library, and to Texas history collections.

Deeds, wills, divorce decrees, and other evidence of the public lives of nineteenth-century women belie the long-held beliefs of their public invisibility. Angela Boswell's Her Act and Deed follows the threads of Southern women's lives as they weave through the public records of one Texas county during the middle of the nineteenth century. Her unique approach to exploring women's roles in a South that spanned the frontier, antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction eras illuminates the truths of the feminine world of those periods, and her analysis of this set of complete public records for those years challenges the theory of men's and women's separate spheres of influence.

The world Boswell reconstructs allows readers a more egalitarian, multicultural look at life: working class and poor women, both black and white, join their more affluent sisters in the pages of the Colorado County, Texas, courthouse records. Those same records reveal that the men of that world—most of them planters or farmers, the majority of them owning at least a few slaves—were a force for women to reckon with, both in public and at home. The almost constant pre-sence of men in the home and their need to uphold the dominant, slave-holding hierarchy produced a patriarchy more pervasive than that experienced by women in the urban North.

Accessible to scholars and general readers alike, Her Act and Deed represents a welcome addition to the classroom, to the scholar's library, and to Texas history collections.

Oklahoma Slave Narratives Index

Oklahoma's Writers Project and Indian-Pioneer History Project for Oklahoma ( 1937- 1938): Copies of original transcripts can be obtained from: Oklahoma Historical Society, 2100 N. Lincoln Blvd. OKC, OK 73105

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ewyatt/_borders/Oklahoma%20Slave%20Narratives/Slave%20Narrative%20Index.html

Slave Narratives, Oklahoma

A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves

by Various Authors English, published in 1941 118,094 words (307 pages)

Oklahoma's Writers Project and Indian-Pioneer History Project for Oklahoma ( 1937- 1938): Copies of original transcripts can be obtained from: Oklahoma Historical Society, 2100 N. Lincoln Blvd. OKC, OK 73105

http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ewyatt/_borders/Oklahoma%20Slave%20Narratives/Slave%20Narrative%20Index.html

Slave Narratives, Oklahoma

A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves

by Various Authors English, published in 1941 118,094 words (307 pages)

From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen's Bureau in Arkansas, 1865-1869

By Randy Finley

Published by University of Arkansas Press, 1996

Original from the University of Virginia

Digitized Jan 15, 2008

ISBN 1557284237, 9781557284235

229 pages

Documenting the difficult class relations between women slaveholders and slave women, this study shows how class and race as well as gender shaped women's experiences and determined their identities. Drawing upon massive research in diaries, letters, memoirs, and oral histories, the author argues that the lives of antebellum southern women, enslaved and free, differed fundamentally from those of northern women and that it is not possible to understand antebellum southern women by applying models derived from New England sources.

By Randy Finley

Published by University of Arkansas Press, 1996

Original from the University of Virginia

Digitized Jan 15, 2008

ISBN 1557284237, 9781557284235

229 pages

Documenting the difficult class relations between women slaveholders and slave women, this study shows how class and race as well as gender shaped women's experiences and determined their identities. Drawing upon massive research in diaries, letters, memoirs, and oral histories, the author argues that the lives of antebellum southern women, enslaved and free, differed fundamentally from those of northern women and that it is not possible to understand antebellum southern women by applying models derived from New England sources.

Negro Slavery in Arkansas - My Readings

Topic: MAJOR TYPES OF FARMING OPERATIONS IN ANTEBELLUM ARKANSAS

Resources: Negro Slavery in Arkansas, Orville W. Taylor Arkansas 1800-1860: Remote and Restless, S. Charles Bolton

Key Facts: There were 4 main types of farming operations in Antebellum Arkansas: (Antebellum means "before the war." In U.S. history it means before the Civil War (1861-1865)

I. Squatter farms (a squatter is a person who settled on vacant land that was owned by the U.S. Government.) These farmers were usually subsistence farmers (those who grew just enough food for themselves and their families). They often settled in the western part of Arkansas, where almost no other white people lived. Usually, these farmers hoped to buy the land from the U.S. Government after they had more money.

II. Yeomen farms with no slaves. (A yeoman farmer was one who owned land, but not very much of it - usually less than 100 acres - and usually didn't have much money.)

This was the most common type of farm in Arkansas at the time. (In the years just before the Civil War started, about 70% of the farms were of this type.) These types of farms were most common in the highlands (in the Ouachita or the Ozark Mountains and the surrounding area.) Yeomen farmers mainly raised corn and hogs.

Even though they owned no slaves, some of these yeomen farmers had close working relationships with those who owned a lot of slaves, and would often sell some of their crops to a plantation with many slaves.

III. Yeoman farms with a few slaves.

These farms were larger than the yeoman farms that had no slaves. Yeomen farmers with slaves had more money than yeoman farmers who owned no slaves. (Depending on whether a slave were male or female, and depending on the age of the slave, slaves in Arkansas usually cost anywhere from $100 to $1,200. The most expensive slaves were usually young adult males. If a slave had a special skill, such as blacksmithing, he might cost even more.)

Usually, a slave owner with just a few slaves was closely attached to them. Even though he owned the slaves and could work them very hard, he usually thought of them as almost being part of his own family.

IV. Large farms run by "planters" (wealthy salve owners who owned 20 or more slaves)

These were wealthy farmers who usually made most of their money by growing cotton (although they also grew other crops, including corn and vegetables). Only about 3% of farmers were planters.

Most Arkansas planters lived in the delta region. (A delta region is a low area along a river that has very rich soil.) In Arkansas, the delta is in the eastern part of the state, along the Mississippi River.)

On plantations (large farms owned by planters) someone besides the planter usually had the responsibility of supervising the slaves. Sometimes this person who supervised the slaves was an overseer - a white man hired by the plantation owner. In other cases, though, the plantation owner would use a slave driver. A slave driver was a slave who was given the responsibility of supervising the other slaves while they worked. Even though the slave driver was himself a slave, he was given a better place to live, better clothes, and more privileges than other slaves.

Most planters owned 20-30 slaves, but some owned a lot more. Elisha Worthington, who lived in Chicot county (SE part of AR), owned more slaves than anyone in Arkansas. In 1860, he owned 543 slaves and 12,000 acres of land.

Many of the larger plantation owners contracted with another man to act as their agent in buying what supplies that were needed (and sometimes to buy more slaves for them also) and selling crops that were produced. Someone who acted as such an agent was called a "factor." A factor wasn't hired as an employee of the planter, but usually was paid a fee that was usually about 2-3% of the total cost of what he bought or sold for the planter.

Sometimes, if a yeoman farmer who lived near a plantation wanted to sell some of his crops and couldn't find a nearby merchant who wanted to buy them, he might get a plantation owner to help him work out an arrangement with the planter's factor.

My Daddy often spoke of the Mason Dixon Line

A Matter of Survival.... for my people...

Slaves had many noteworthy skills and talents which made plantations economically self-sufficient. The services of slave blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, shoemakers, tanners, spinners, weavers and other artisans were all used to keep plantations running smoothly, efficiently, and with little added expense to the owners.

These same abilities were also used to improve conditions in the quarters so that slaves developed not only a spirit of self-reliance but experienced a measure of autonomy. These skills, when added to other talents for cooking, quilting, weaving, medicine, music, song, dance, and storytelling, instilled in slaves the sense that, as a group, they were not only competent but gifted.

Slaves used their talents to deflect some of the daily assaults of bondage. They saw themselves then as strong, valuable people who were unjustly held against their will rather than as the perpetually dependent children or immoral scoundrels described by so many of their owners. Indeed, they found through their artistry some moments of happiness, particularly by telling tales which portrayed work in humorous terms or when singing satirical songs which lampooned their owners...

These same abilities were also used to improve conditions in the quarters so that slaves developed not only a spirit of self-reliance but experienced a measure of autonomy. These skills, when added to other talents for cooking, quilting, weaving, medicine, music, song, dance, and storytelling, instilled in slaves the sense that, as a group, they were not only competent but gifted.

Slaves used their talents to deflect some of the daily assaults of bondage. They saw themselves then as strong, valuable people who were unjustly held against their will rather than as the perpetually dependent children or immoral scoundrels described by so many of their owners. Indeed, they found through their artistry some moments of happiness, particularly by telling tales which portrayed work in humorous terms or when singing satirical songs which lampooned their owners...

(this is a quote taken from various internet readings... please forgive me that I did not save the point of reference in order to give other writers their credit....... the reading touched me and I copied it as such.... yours truly - B Kirk)

Hagar Brown, former slave at The Oaks plantation, Georgetown County, South Carolina (13.5)(Photograph by Bayard Wootten, ca. 1938)

Down in the quarters every black family had a one- or two-room log cabin. We didn't have no floors in them cabins. Nice dirt floors was the style then, and we used sage brooms. We kept our dirt floors swept . . . clean and white.-- Millie Evans, former slave from North Carolina

In the cabins it was nice and warm. They was built of pine boarding . . . . The beds was made of puncheons [rough poles] fitted in holes bored in the walls, and planks laid across them poles. We had ticking mattresses filled with corn shucks. Sometimes the men build chairs at night. We didn't know much about having nothing, though. -- Mary Reynolds, former slave from Catahoula Parish, Louisiana

My father was a carpenter and old massa let him have lumber and he made he own furniture out of dressed lumber and make a box to put clothes in. And he used to make spinning wheels and parts of looms. He was a very valuable man.-- Carey Davenport, former slave from Walker County, Texas

Down in the quarters every black family had a one- or two-room log cabin. We didn't have no floors in them cabins. Nice dirt floors was the style then, and we used sage brooms. We kept our dirt floors swept . . . clean and white.-- Millie Evans, former slave from North Carolina

In the cabins it was nice and warm. They was built of pine boarding . . . . The beds was made of puncheons [rough poles] fitted in holes bored in the walls, and planks laid across them poles. We had ticking mattresses filled with corn shucks. Sometimes the men build chairs at night. We didn't know much about having nothing, though. -- Mary Reynolds, former slave from Catahoula Parish, Louisiana

My father was a carpenter and old massa let him have lumber and he made he own furniture out of dressed lumber and make a box to put clothes in. And he used to make spinning wheels and parts of looms. He was a very valuable man.-- Carey Davenport, former slave from Walker County, Texas

A Fine Weaver

Lucindy Jurdon, former slave from Georgia (21.2)

(Photograph possibly by Preston Klein and Jack Kytle, ca. 1938)

Lucindy Jurdon reported to her interviewers:

Lucindy Jurdon reported to her interviewers:

"My mammy was a fine weaver and she work for both white and colored [people]. This is her spinning wheel, and it can still be used. I use it sometimes now."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)